Delta sleep-inducing peptide (DSIP) is a short peptide of natural origin. It gains its name from its ability to cause sleep in rabbits and from the fact that it was first isolated in 1977 from the brains of rats during slow-wave sleep. The peptide, however, has a number of physiologic and endocrine roles that are slowly being uncovered as it gains interest among researchers. Right now, it is known that DSIP can alter corticotropin levels, inhibit somatostatin secretion, limit stress, normalize blood pressure, alter sleep patterns, and alter pain perception. It may also have future applications in cancer treatment, depression, and the prevention of free radical damage.

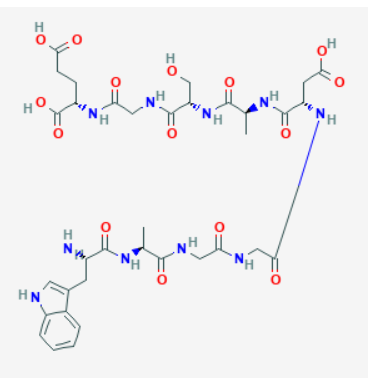

Sequence: Trp-Ala-Gly-Gly-Asp-Ala-Ser-Gly-Glu

Molecular Formula: C35H48N10O15

Molecular Weight: 848.824 g/mol

PubChem CID: 68816

CAS Number: 62568-57-4

Synonyms: Emideltide, DSIP nonapeptide, Deltaran

Despite its name, the connection between DSIP and sleep has been difficult to pin down. Following the initial study in rabbits, DSIP has undergone extensive investigation to determine its effects on sleep. Unfortunately, a pattern has been difficult to isolate. In some studies, DSIP promoted slow-wave sleep and suppressed paradoxical sleep. In other studies, DSIP has had no impact on sleep at all. In one study, DSIP was found to cause arousal during the first hour of sleep followed by sedation starting in the second hour of sleep[1]. Overall, this study suggested that DSIP helps to normalize sleep and regulate dysfunction in sleep cycles, effects which tend to be corroborated by other research.

Perhaps the most significant sleep research involving DSIP has been performed in the setting of chronic insomnia. In this particular example, the peptide appears to improve sleep enough to match that of normal controls[2]. These findings are reflected in other studies showing that DSIP improves sleep structure and reduces sleep latency in chronic insomnia. Overall, polysomnographic studies indicate higher sleep efficiency with DSIP that, while statistically significant, is still relatively weak[3].

Despite the contradictions in the research, it is almost impossible to deny that DSIP is in some way related to sleep onset. Research in human subjects has uncovered a number of subjective measures indicating that DSIP promotes sleep. For instance, DSIP produces feelings of sleepiness, increases sleep time by 59% compared to placebo, and shortens sleep onset. These subjective findings, however, are almost perfectly contradicted by EEG analyses that show no obvious sedation[4]. The problem, however, may by with current testing methodologies as many EEG measures of sedation are based on pharmacologic sedation and not natural sedation. At the very least, DSIP offers a new and useful tool for reevaluating how we measure sleep in the laboratory. It may help scientists to develop a more thorough understanding of human sleep, a physiologic function that is still shrouded in a great deal of mystery despite more than a century of dedicated research.

Analgesic control can be difficult in the setting of chronic pain. Current medications, such as NSAIDs and opiates, while effective in the short term, can have serious side effects when used for too long. Current analgesics are best suited to the short-term treatment of pain, so researchers have sought an alternative for treating chronic pain syndromes. A small pre-clinical trial in humans has found that DSIP can significantly reduce pain perception and improve mood. This same study found that DSIP may be useful in patients with a physiologic dependence on other pain medications as it helps to reduce withdrawal symptoms and the pain rebound that often occurs following cessation of long-term analgesic therapy[5].

Research in rats suggests that DSIP acts on central opioid receptors to produce its analgesic effects. It isn’t clear if these are direct or indirect effects, but the peptide produces a significant pain-relieving effect that is dose dependent[6]. There is no indication that DSIP produces the kind of dependency that opiate medications do despite the fact that both work on the same receptors in the central nervous system.

Research in rats indicates that DSIP alters the stress-induced metabolic disturbances that often cause mitochondria to shift from oxygen-dependent respiration to oxygen-independent respiration. The latter is much less efficient and is associated with the production of toxic metabolic byproducts. The ability of DSIP to maintain oxidative phosphorylation, even in the setting of hypoxia, could make the peptide a useful treatment in conditions like stroke and heart attack. By preserving normal mitochondrial function, DSIP could help to offset the metabolic damage caused by oxygen deprivation and protect tissue until proper blood flow can be reestablished[7].

These properties would make DSIP a very powerful antioxidant and one that works at the most basic level of free radical production. By preserving normal mitochondrial function, DSIP reduces the production of free radicals. This may make it a potent anti-aging supplement, though much more research is required to understand the exact effects of the peptide.

The finding that DSIP can alter mitochondrial activity in hypoxic settings led scientists to investigate the mechanism by which the peptide has this effect. It turns out that DSIP restricts changes in monoamine oxidase type A (MAO-A) and serotonin levels[8]. This finding, of course, suggested to the researchers that the peptide may have an impact on the course of depression.

Analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid of patients suffering from major depression has revealed decreased levels of DSIP compared to controls[9]. Given the strong link between sleep and depression, it should come as no surprise that a peptide involved in regulating sleep cycling could also play a role in the development of depression. To date, there has been no attempt to treat depression by normalizing DSIP levels[10]. The peptide, has, however, been linked to changes in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and may play a role in suicidal behavior[11].

A lot of cancer research focuses on curing the disease once it has been diagnosed. A smaller, but growing segment of researchers, however, are interested in preventing cancer from developing in the first place. The majority of focus is on stimulating the immune system, via a so-called cancer vaccine, to seek out and eliminate cancerous cells before they spread. Research in mice, however, suggests that DSIP may have better cancer prevention effects than any vaccine tested to date. In the study, female mice were given DSIP on 5 consecutive days of every month starting at the age of 3 months and persisting until their death. Treated rats showed a 2.6-fold decrease in the development of tumors. This remarkable reduction in cancer occurrence was accompanied by a 22.6% decrease in the frequency of chromosomal defects in bone marrow[14].

One of the side effects of chemotherapy is changes in central nervous system functioning. These changes can include impaired motor control, behavioral alterations like depression, and problems with language. Children undergoing chemotherapy are especially vulnerable to CNS alterations following cancer treatment. A recent study suggests that DSIP can correct these CNS alterations or prevent them from occurring in the first place[15]. At least part of this effect may be explained by the selective effects of DSIP on blood supply to the brain. Research in rats indicates that DSIP and its alternative preparation Deltaran, increase blood supply significantly in the setting of CNS stresses like ischemia and chemotherapy. In fact, in an animal model of cerebral ischemia, animals given Deltaran survived 100% of the time compared to just 62% of controls[16]. By boosting blood flow in the brain, DSIP can encourage healing and reduce metabolic damage.

DSIP was first found in the brains of rabbits during slow-wave sleep and has since been associated with sleep and central nervous system regulation of sleep-wake cycles. Interestingly, however, is the fact that no one knows where or how DSIP is synthesized. Levels of DSIP are as high in peripheral tissues as they are in tissues of the CNS, suggesting that the peptide may be made outside of the CNS and that its primary function may not involve sleep at all.

There is also speculation that DSIP may be a hypothalamic hormone that regulates more than just sleep in the same way that growth hormone, for instance, regulates more than bone and muscle growth. In one study, DSIP was found to inhibit somatostatin, a protein produced in muscle cells that inhibits muscle growth[17]. By inhibiting somatostatin, DSIP contributes to hypertrophy and hyperplasia in skeletal muscle. These direct inhibitory effects seem odd for a peptide originally thought to be primarily involved in sleep promotion. This has led some scientists to speculate that research has missed the mark where DSIP is concerned and that the peptide might have a larger, more universal role in regulating human physiology.

Further contributing to the idea that DSIP may be more than CNS peptide is the fact that it has been found, in animal models, to regulate blood pressure, heart rate, thermogenesis, and the lymphokine system. Some of these effects appear before any clinical or laboratory signs of sleep, indicating that DSIP may actually play a role in altering physiology to prepare the body for sleep onset[18].